Let’s Talk Sabre Rules

Hello!

Kat, here. Many of you know me as the very official social media correspondent for HSS. That means I help Dan and Liz with the Facegrams and the Instabooks. Some of you also know me as that person that brings in a lot of baked goods. I also have fenced saber (the weapon formally known as sabre) for a good number of years.

Recently Dan asked me to think about possibly reffing saber at our upcoming tournament, the Brash Bash (“Kat, was that a blatant plug to the tournament?” Gasp, I would never!). Now, just like foil, saber is a priority weapon, and for many is a daunting task to think or even talk about when it comes to reffing. Everything is up to the ref’s opinions, and you can bet the farm on the fact that fencers will want to fight calls if they think you’re willing to give in. It’s not meant for the faint of heart or easily guilted. But, I feel that information is power, and this would be a good chance to go over some of the “oddball” things you can do with rules in saber. It’s good as a fencer, a parent, or a ref to know what you can’t (and can) get away with.

Let’s hop right to it!

The New Saber Lines

If you didn’t already know, in the 2016 season, saber was given a new place to stand on guard for the start of each bout. It was a “testing” period as the committee thinks about changing up the rules a bit. It has it’s pros and cons (and people who whine about it, myself included), but here’s what the details are.

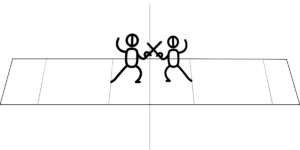

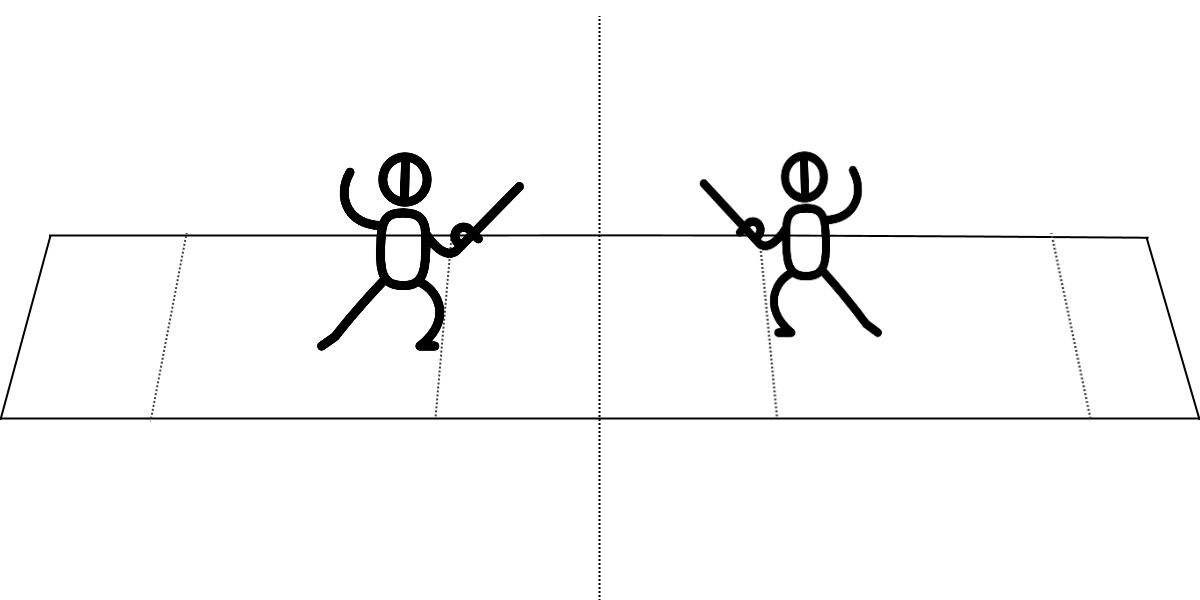

This is how we used to start our bouts:

Alright lookin’ good, lookin’ good. How does it look in the testing period?

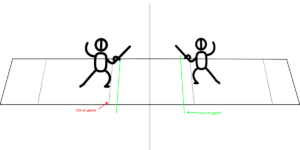

Yowza! That’s close.

(Do people still say yowza? I know so very little of what is “hip” now.)

Okay, obviously this isn’t up to scale, but we tested starting with our back foot on the en guard lines. For most people this isn’t a problem, especially when you’re short like I am and have the leg length of an adult male corgi. But for seriously tall fencers, or ones who have grown familiar with a particular rhythm or beat when attacking off the line, this is a big change! When you’ve done drills and lunges with a particular distance in mind for many years, it’s hard to wrap your mind around.

Here’s what it looks like in action:

Ah, so graceful.

But after the testing period was over, the committee has decided to have the lines 3 meters apart. That is, a second line 50 cm in front of each existing en garde line, where the saber’s front foot will sit behind it. Therefore, you’re still closer to your fellow fencer, but you’re not focusing on your back foot as a guide.

Point in Line

Point in line is one of those things an opposing fencer can do to you. It’s right along the lines of ducking or squatting to avoid a touch, and it’s typically something I see when a fencer has been fencing for just about that sweet spot of over 6 months. They get the hang of things, get some confidence, and they think they’re going to be clever.

Now, lets first talk about what it is. Here’s what the rules book says:

The point in line position is a specific position in which the fencer’s sword arm is kept straight and the point of his weapon continually threatens his opponent’s valid target.

In other words, the fencer has reached their arm out to point his weapon towards the valid target area (the lame, mask, etc), and the entirety of his arm is straight and in line with his weapon. But, in context this usually means the chest. If you point to their lower stomach or belly, it probably won’t be called as a point in line.

Also, that last part tricks up some fencers. If the saber is pointed in a non direct manner, the ref can call that you were just standing there and not using your weapon, as the rule book says, to “threaten”. The hand is rotated to a prorated position within the line, and thumb on top isn’t a good sign either. If I’m looking straight at the fencer with a point in line, I shouldn’t be able to see their elbow or arm, it should be basically a dot. Or, in other words, it would be the exact same position your shoulder to arm to weapon would be if you had finished an attack. That’s the logic here, is that you’re basically attacking your opponent, but doing so in a still manner, and it’s threatening/super duper scary. So, if you want your point in line to be a boogey monster (which you do), don’t twist your wrist or bend your arm so that it isn’t a straight line.

(Source)

Now, what does this do in a bout with rules?

Lets say the Red fencer (fencer on the left) starts a point in line and after the Green fencer (fencer on the right) attacks, and both lights go off. Let’s say that Red’s point in line is never broken, meaning that his blade and arm never twist or twirl or etc and his feet never change it up, then he has been attacking this whole time like one giant slo-mo movie. That means Red fencer will get the point.

Now, same scenario, but Red moves back and forward, drops his hand, checks his email, and brings it back up? He won’t get that point. He broke the line, and “stopped attacking”. You have to keep the line straight the entire time. What if the Green fencer hits his blade? Expect a parry ripost, beat attack, or counter as your result. If you’re looking for a way to trip up a new fencer, break the tempo, or just be “clever”, do a point in line properly.

What should you do if someone does a point in line to you? If you get them to break the line, or move their hand, then you’ve gotten them to break the attack. And, you are being threatened. Get them to react the same way you would if you were attacked on strip in a traditional sense.

Attack in Prep

This one can ruffle some feathers. So often do I see newbie fencers get in their first tournament, attack with vigor, and not understand why the call wasn’t to them.

First, let’s show what ye olde rule book says.

Actions, simple or compound, steps or feints which are executed with a bent arm, are not considered as attacks but as preparations, laying themselves open to the initiation of the offensive or defensive/offensive action of the opponent.

What does this mean? Well, it’s really just saying that what you think of as attacking isn’t as clear and obvious as a threatening attack, or at least not to the ref (Usually I find slipping the ref a cookie will change this opinion. Make sure it’s something high quality like chocolate chip.). But really, what the ref is saying is that yes, the fencer is moving forward and clearly is trying to attack. But, their form is not showing all of what it would take be a proper attack. The hand isn’t reached out, the body is leaning back, or a variation.

A preparation is also an action designed to draw a response from an opponent. So, if you see your opponent doing this, try to make sure you’re ready for whatever second action they have up their sleeve.

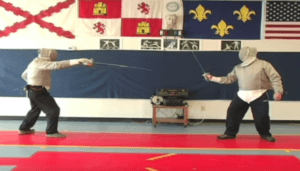

Let’s look at some photos from our page to see what was a prep, and what was good!

This is from the Brash Bash last year (oh, whoops! This link to our next Brash tournament fell here. How did that happen??). See the fencer on the left? He’s clearly making an attack overall. He’s reaching out with his foot, moving forward, and trying to gain ground. But he’s also winding up his weapon hand, and it’s not reaching out towards his opponent. To some refs, this could be considered a preparation. He’s not “fully committed” to this attack, and it could be considered as “not threatening”. You’ll notice that theme in the rules. It’s all about who is threatening and who is dominating the action on the strip.

Let’s see a good attack now.

See the fencer on the right? He’s definitely showing an intention to attack. His arm is reaching out, he’s pushing off his back leg, and extending his front leg. He would never have a prep called on him here.

Now this last one I would call…. special? Special.

Your parry, my beat?

Many times, saber fencers have been fencing, do a parry riposte, and expect the point to go to them. Instead, they get the disappointment trombone and walk away with a frowny face with it called a beat attack.

So what makes a beat attack a beat attack? Ye olde rule-book knows.

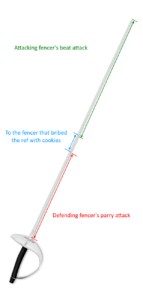

In an attack by beating on the blade, this attack is correctly carried out and retains its priority when the beat is made on the foible of the opponent’s blade, i.e. the two-thirds of the blade furthest from the guard.

That means, a beat is when you’re attacking and you hit your opponent from the two 2/3rds of the blade. If you hit the bottom third of their blade (guard included!), it will be interpreted as the other fencer’s parry.

So if I parry my opponent, and my parry is done by me hitting their blade with my weapon’s tip or top section? It’s going to be called their beat. But, if they have the right of way, and attack me on my guard or lower section of the blade, it’s my parry (even if I didn’t really make a parry type of movement).

Here’s a helpful diagram:

So, if you want to make a parry (or a beat), you must make your actions very clear to the ref (like usual). But, usually I find a ref will give the bottom half of the weapon as a parry, since it’s clear that is what your action intention is.

Lastly, it’s the ref’s call

Remember, it’s really up to the referee. If they sneeze, get dust in their eyes, or get distracted, and see something different than you, that’s what they’ll call. The best course of action is to always be polite, and ask for clarification. Most refs actually like explaining their call, and appreciate that you’re invested in your sport.

I hope you all learned something today! If not, feel free to join us at a class, or email us with more questions about fencing rules.